The rains have subsided, the winds are cooler and days are getting shorter - it is Dostoevsky re-reading season! The last time I read Crime and Punishment was three years back. For Legal Methods, in my first semester of law school, our Professor gave us full creative freedom - write about anything our heart desired, but try to inculcate some legal elements in it. Naturally, I wrote about the best piece of literature I had ever read, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. In 2021, I read the book twice and I emerged as a new person every time I read it. Any work written by Dostoevsky, Tolstoy or Orwell is meant to be devoured again and again. Their brilliance magnifies with every season.

Last night, with the house quiet after submitting my work, a delightful breeze wafted through my balcony. I was at ease - and then immediately my body pushed me to pick up Crime and Punishment again. Something stirs in my brain, and I ruminate involuntarily before I decide to re-read a book again. By 3 am the decision was made, I will immerse myself in Raskolnikov’s world for the next few weeks.

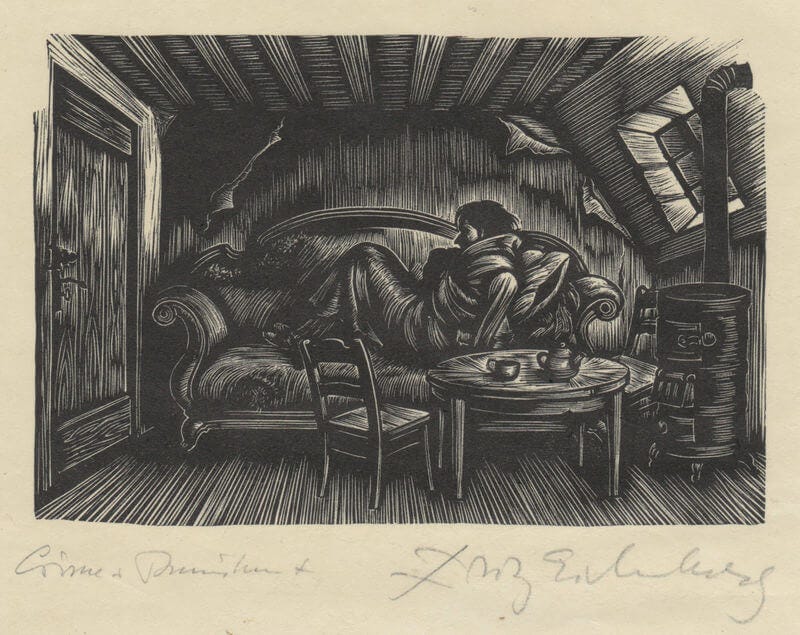

Therefore, there could have been no better time for my to revisit this essay again and send it out in the void - as a precursor to the journey I will take with Dostoevsky. Enjoy!

The protagonist of the novel Crime and Punishment, Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov, an ex-law student, murders his pawnbroker. In his case, there are layers to the motive behind his crime.

Firstly, he murdered Alyona Ivanova to find an easy way out of his abject poverty. The novel despairingly describes the wretchedness of St. Petersburg. Children are starving, young girls are assaulted, Raskolnikov’s own sister is preyed upon and is forced into a marriage due to their pathetic financial conditions. All these deplorable conditions initiated a deep hatred of society in his mind.

He had been in an overstrained irritable condition, verging on hypochondria. He had become so completely absorbed in himself, and isolated from his fellows that he dreaded meeting anyone at all. He had given up attending to matters of practical importance; he had lost all desire to do so.

Viewing Raskolnikov’s offence through the ‘Social Contract’ theory of Jean Jacques Rousseau makes it a valid and natural consequence of detachment from society. The European philosopher’s famous treatise begins, ‘Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains’.

A believer of primitive behaviour dating to the origin of society and simple virtues, Rousseau attributes the beginning of crime and degeneration of human beings to civilisation. While he expounds that man is free and good by nature, social associations due to civilisation like family and friends lead to jealousy and vices which create a hierarchical structure of inequality.

He declares that to achieve absolute equality and independence, it is imperative to go back to the primitive stage which is not possible now without a sovereign governing the social associations.

A natural legal theory, ‘Social Contract’ emphasizes a group identity gaining importance over an individualistic identity. In a trade-off with the sovereign, the common people give up their individual rights and freedom for the protection of their common identity. Every member of the sovereign is bound to other individuals of the sovereign and in this way, Rousseau traces the power of authority to the people. Like the theory of legal positivism, this is dependent on the social acceptance of the sovereign.

One is bound to obey the laws if there is common acceptance of the authority. However, what happens when an individual disobeys the common will of the association?

Raskolnikov is slowly alienated from the moral fabric of society and starts viewing himself not as a member of Rousseau's sovereign but as an outsider. This feeling of not belonging in the realm of society leads him to reject the authority of the common, political association and therefore, unbounds him from obeying the laws which regulate individual behaviour.

Yet murdering the pawnbroker to steal a meagre amount of money was just a facade of the real intention behind his crime. Raskolnikov was the propounder of the ‘Bad Man Theory’. He believed that people could be divided into ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’. The ‘ordinary’ men had to live in submission to both law and morality whereas the ‘extraordinary’ could bypass ethical values and fair justice to achieve greatness. He even maintains that the loss of a few lives is acceptable if it is for the greater good of the maximum number of people. The Übermensch or the superman is duty-bound to transgress the law - in fact to achieve greatness, he must commit a crime. His theory is synonymous with what the analytical or positivist school of law professes.

Founder of the ‘Principle of Utility’, Jeremy Benthem said the main purpose of the law is to provide the greatest happiness to maximum people. By ignoring the subjectivism provided by morality in other political theories, utilitarianism focuses on objectivism which may lead to the sacrifice of a few individual’s rights.

Any action can be quantified as the amount of pleasure or pain it brings to an individual whose interest is in question, as ‘it is pointless to talk of the interest of the community without understanding what the interest of the individual is.’ Therefore, any action which increases the collective happiness in society is said to be in conformity with the utilitarian theory.

Raskolnikov considers the pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanova a ‘leech’ of society, greedy and useless. He professed that by murdering her, he bestowed a great benefit to society and the world would be a better place without her. This false inflation of his responsibility to rid the world of a character deemed worthless by him was Raskolnikov’s utilitarian motive.

It is the Ubermensch theory that instigates him to test whether he belongs in the ‘extraordinary’ category of men. Imagining himself to be above the rest of mankind and immune to the moral consequences, his failure to rise above the wretched feelings which follow the crime, discredits his beliefs.

As he confesses to Sonia, he explains, ‘I only wanted to dare.’

He is indifferent to the legal sanctions which await him; instead, the deep-rooted immorality and guilt of the crime haunt him and lead him to extreme paranoia.

I wanted to murder without casuistry, to murder for my own sake, for myself alone! I didn’t want to lie about it even to myself. … I wanted to find out then and quickly whether I was a louse like everybody else or a man.

Raskolnikov does not contest the legal consequences of his crime. He believes in the law’s ultimate sovereignty and accepts his imprisonment, due to his unfortunate realization that he was just an ordinary man who does not have the right to transgress the law.

The command theory of Austin states that the threat of sanctions is what differentiates law from non-law. Morality is irrelevant and the validity of a law depends on whether the state thinks it is valid. Only two conditions are to be fulfilled for the creation of law; whether it was created by the correct authority and whether the authority followed the correct procedures.

Raskolnikov’s verdict and sentence were valid as they arose from a legally sanctioned authority, irrespective of the fact that he did not think his act was immoral. However, he is unable to bear the total alienation he has brought on himself, and the mental anguish makes him realize he cannot separate himself from society for his own sustenance. Therefore, his complete submission to the law leads him to hope for redemption and a chance to be free again, morally.

Raskolnikov’s crime has many layers and motivations, and this is synonymous with crimes that take place in the current world. No single theory of law can accurately capture the mens rea behind an offence whose motive is deep-rooted in the unconsciousness.

By dissecting the murder committed by Raskolnikov according to different schools of thought, it can be seen that theories of jurisprudence can bring us closer to understand the political, societal, moral and philosophical influences which affect the legal system and why it is necessary to debate these ideas in legal theory.

(I firmly believe in enriching my reading experience with an immersive soundtrack tailor-made for the book)